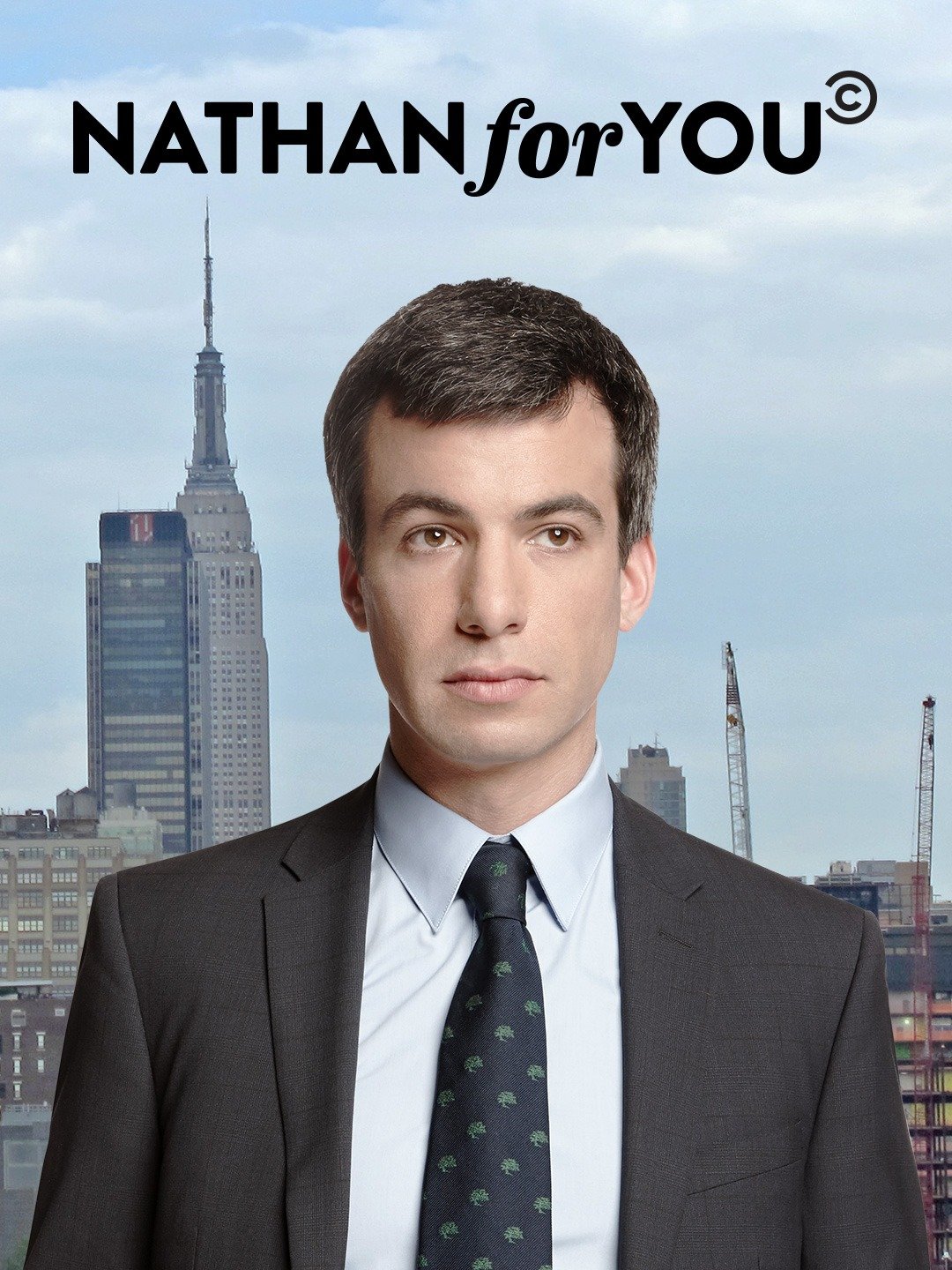

Throughout this week’s reading, I could not help but be reminded of comedian Nathan Fielder, particularly as his work pertains to the key tensions between rascal and victim and reality and artifice in humor. Fielder’s first major success, the Comedy Central-backed docu-reality comedy series Nathan for You, follows Fielder as a characterized version of himself providing outrageous advice to small businesses to test the limits of people’s willingness to yield to social pressure and go along with what they sense is wrong. While much of the humor lies in Fielder’s own awkwardness and absurdity rather than the pure victimization of another person, the show adheres to the traditional duality of “rascal” and “victim” in which Fielder is the empowered mastermind of a rascal (Gunning 90). A key feature of the rascal is his—and, notably, the character role is emphasized as “boyish” in the literature—simultaneous impishness and innocence. The winking, childlike nature of the role builds a mythos around the rascal that ascribes a certain invincibility. While “tricksters may themselves become butts of the joke, or have it turned against them,” the punishment does not permanently rob them of their charm or the loyalty of the audience (Gunning 92). It seems a crucial element of the rascal’s impermeability is his rebellion against authority; without this subversion, pranks and gags could more often teeter into cruelty than amusement. In this sense, Fielder’s work is not without criticism. Nathan for You targets small businesses that are vulnerable in their desire for help and thereby “depends on the participation of people who are struggling, many of them immigrants and people of color” (Shapiro). The social humiliation central to gags and pranks must operate conscientiously, and how to do so is often contentious as Fielder himself admits to sometimes “get[ting] it wrong” with the handling of the murkiness of his pseudo-reality work (Shapiro).

While the sources of social humiliation in classical Hollywood silent comedy are largely physical gags, Fielder’s schemes are profoundly psychological. In his more recent show, HBO’s The Rehearsal, he aims to expose hairy truths undergirding our social landscapes and people’s innermost psyches. The Rehearsal evolved from the amusement Fielder found in tirelessly trying to predict, control, and plan for every possible reaction in Nathan for You. In The Rehearsal, Fielder enlists participants to engage in impossibly detailed simulations of anxiety-inducing situations to prepare them for any outcome—for example, a man confessing to his trivia team that he has been lying to them for years about his credentials, a woman practicing parenting to see if she wants to have a child, and a man seeking to confront his brother about their grandfather’s will. Admittedly, I have not seen the entire show so I lack the context of its entirety. Still, in the middle of the season, Fielder himself begins rehearsing, appearing at least within the show’s diegesis to have pierced his own invincibility as a rascal. Fielder sees himself as the most “pathetic” person on screen, complicating the relation between rascal and victim (Shapiro). Much of what is comical rather than comedic is in Fielder’s own disposition and quirks rather than the constructed situation with the participants, something he did not entirely expect (Shapiro). The line between Fielder-as-character and Fielder-as-producer is constantly in question as the audience is never sure how truly real the show is. While he is highly anxious and self-conscious, the show is his constructed reality as a producer, so despite any expressed self-reflection or worry from the character of himself, ultimately he is still the rascal in control. This ambiguity of the performance of the self and feigned reality is heightened in spheres like Youtube and TikTok where creators crave and survive off of audience approval of their performances of authenticity (Jenkins 2006). What the amusement and, at times, the stress of watching Fielder’s work demonstrates is that these desires and fears are more central to human experience than symptomatic of these specific platforms. While the social media age has indubiously fueled anxiety and performance culture, it by no means invented it, in the same way that early silent comedy also reproduced existing comedic forms. Insofar as what is funny is what is at least partially true, the precariousness of our construction and experience of our reality is essential to our experience of humor and comedy’s development as an industry operating in an ever-complex social landscape.

Works Cited

Gunning, Tom. “Crazy Machines in the Garden of Forking Paths.” Classical Hollywood Comedy. Edited by Kristine Brunovska Karnick, Henry Jenkins, 1st ed., Routledge, 1994.

Jenkins, Henry. “Youtube and the Vaudeville Aesthetic — Pop Junctions.” Henry Jenkins, http://henryjenkins.org/blog/2006/11/youtube_and_the_vaudeville_aes.html. Accessed 15 Jan. 2023.

Shapiro, Lila. “Nathan Fielder Is Out of His Mind (and Inside Yours).” Vulture, 5 July 2022, https://www.vulture.com/article/nathan-fielder-rehearsal-profile.html.

I really like the point that you brought up about how the tricksters, or rascals, can sometimes be the butt of the joke or have it flipped on them. I think this form of comedy – in which a the rascal is the target of mockery through their inept social skills or lack of conformity to social norms – is becoming increasingly popular in the modern age of comedy film.

“I Think You Should Leave” with Tim Robinson or “Curb Your Enthusiasm” with Larry David remind me of Nathan Fielder’s comedy and how the rascal ends up being the butt of the jokes. In fact, I would go as far to say that the most common and (in my opinion) best forms of comedy in a character are those who frequently get laughed at, not with. Typically this character is the dumb or clumsy one in the cast; your Joey Tribbiani or Micheal Kelso’s of television often provide a guaranteed laugh at the expense of their integrity/intelligence. It is fascinating that the rascal being the butt of the joke seems to be the more prominent formula for comedy now, and I wonder why this has shifted in this way over the course of film history.

I found your analysis of Nathan Fielder’s comedy as ‘the rascal’ to be particularly insightful to me, because it made me think further on the specific persona which Nathan Fielder himself has produced over the course of his career in TV comedy. When we’re watching Fielder attempt to fix businesses, or perversely infiltrate a participant’s life for his persona’s unorthodox fixations, we’re not entirely sure whether Fielder’s victims are aware he’s putting on an act, or they’re all part of a greater act of greatly convincing improv – Fielder would seem to trick us at every turn. What particularly cements Fielder as ‘the rascal’ for me, however, is his youtube video entitled ‘dance’ – which I believe to be an attempt from Fielder to trick us further into believing his persona from television by appealing to the domesticity of youtube, thereby feeding the greater illusion of his comic persona.

I think your association of Nathan Fielder as the rascal is awesome! Your point about Fielder using his own vulnerability as a means of complicating that role is what makes him a very captivating television producer.For me, he is one of the most original TV personalities/writers working today and I think its fascinating to consider the way that he assumes the role of the rascal I also think that his work can serve as an extension of Gunning’s interpretations regarding gags and interruption. While Nathan For You largely demonstrates a dissolution of the narrative format that would seemingly uphold the idea that gags are discontinuous and after one has concluded the machine must start up again, The Rehearsal generates a majority of its comedic value from the completely opposite direction. Most of the absurd humour on display in The Rehearsal comes from Fielder producing a show that is almost painstakingly serial and directly told from the (at least somewhat fictionalised) perspective of Fielder creating a show based off of a practice that he actually employs to help him with his anxiety. His unfailing comitment to his concepts in both shows creates some truly bizarre moments and many of the funniest scenes come from the non-actors interacting with Nathan as he reveals his absurd plots. The Rascal/Victim dynamic is also particularly interesting in both shows because, as you pointed out, pretty much every scene ends with Fielder making things awkward or outright angering the people he is purportedly attempting to help. It is a fascinating development on the idea that Gunning identifies about how the Rascal often has the mischief turned on him, wherein practically every joke in either of Fielder’s series boil down to him being conversationally uncomfortable and not very good at his job.

I really like how you elaborate on the rascal and victim relationship and build on the ideas in the key reading to discuss wider questions about morality and authenticity as well as just how Nathan for You and The Rehearsal work on a comedic level. For me, this highlights how comedy is not always about the humorous element and perhaps suggests that as well as looking on the mechanisms of comedy and the gag itself, it is important to consider wider implications and effects on audiences and on the ‘victims’ of the gag, especially in a non-fiction film. I think this is especially pertinent now as we re-evaluate what has previously been acceptable in comedy and recognise that certain types of humour or jokes which were acceptable in the past would not be made today.

I love the line about creators craving and striving off of audience approval of their performances of authenticity, and the fighting notions of Fielder’s power as a producer and innocence in the character he puts on. Especially when it comes to Tik Tok, it seems easy to put on a persona that is not the truth in who you are — we see a lot of very famous and well-liked creators being outed for being bullies in high school and their history not matching up with the online persona they’ve created. When you have a platform, it’s important to use that platform responsibly, and I think this concept of Fielder’s power in manipulation and persona of ignorance to the truth of his work is a very real phenomenon within the people among us. But also, love Nathan for You.